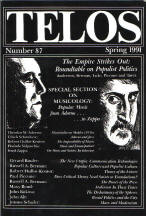

Telos

1991 Spring

No. 87

(1) Introduction: Popular Music from Adorno to Zappa

By Russell A. Berman and Robert D'Amico, pp 71-78

(2) The Mother of All Interviews: Zappa on Music and Society

By Florindo Volpacchio, pp 124-136

(1) [....] The interview with Frank Zappa is particularly useful antidote to the all too common academic pretensions concerning the status and significance of popular music. Zappa continually reveals how the processing of music for market distribution has nothing whatsoever to do with aesthetic imperatives, radical political messages, or personal self-expression. His realism about these matters puts into question not only affirmative accounts of popular music by fashionable radicals, but Kentor's more sophisticated effort to ferret out disruptive challenges buried deep within the musical syntax. [....]

(2) Volpacchio: I would like to begin by asking what you think of Adorno's music.

Zappa: [The music] sounds like what happens if you tried to write something just like Webern and filled in all the empty spaces. Some of the things I liked, but I liked them because they reminded me of Webern. The choral piece was son of Das Augenlicht and there is an orchestral piece in there that sounds like it could have been from Webern's Five Orchestral Pieces. The piece I liked the best was the most old fashioned one, the tonal chromatic piece. It sounds more like what Wagner would have sounded like if he knew what he was doing. It reminded me of a cross between Wagner and Fauré. The other stuff seems to be aesthetically in the region of Webern's aesthetic with the aroma of Berg minus the turgid flux. You can think of it as enjoyable Schoenberg. But it did not come off to me as scholastic.

I thought there was a Webern aesthetic, harmonically and melodically [in most of the music]. But the thing that wasn't Webern was how it filled up all the spaces. I did not hear any forward looking compositional ideas there because everything that I had heard, with the exception of the earliest – I presume it was the earliest – piece, the one that was the most melodic, were all things I had heard in one form or another in the music of the Viennese School. If I had more familiarity with the music of Schoenberg, I could probably point out the names of the pieces that sounded like they were clones. I am more familiar with all the Webern pieces, and I just heard a lot of things in there that sounded very derivative of Webern. I don't know who did the work first. (read more)