NON-FOODS

NON-FOODS

Stretching Out With Vamps

By Frank Zappa

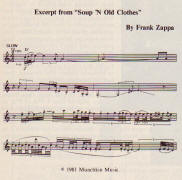

THE WRITTEN MUSIC TO "Soup 'N Old Clothes" [Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar, Barking Pumpkin Records, BPR 1111] looks much scarier than the piece sounds.

Yeah. [Composer] Karlheinz Stockhausen had a word, or an expression, to describe musicians' reactions to difficult-looking music. He said that they create lazy dogmas of impossibility. It's only the young kids that will take on the challenge and do it. I mean, I've worked with a lot of older musicians from time to time, and they're totally resistant to reading anything faster than a sixteenth-note. They just don't want to know about difficult rhythms, whereas the younger kids are interested in them. This enters into many facets of our lives. For instance, a kid can sit down at a computer and just wail on it. Kids aren't hung up on the orthodoxy; they just want to go in there and make something happen with the knobs and dials. And I can't blame them. "Soup 'N Old Clothes" has a lot of sixty-fourth-notes in it. Listen to the tempo. These notes are pretty fast even at that tempo. Once again, it just goes to show how Steve Vai transcribes the stuff.

"Soup 'N Old Clothes" is a good example of a vamp – a repeating chordal accompaniment – at work.

"Soup 'N Old Clothes" is a good example of a vamp – a repeating chordal accompaniment – at work.

Well, that's to anchor the listener's ear. It gives them something to tap their foot to. Then the rest of what's being played is an extrapolation beyond that. If I were playing the same thing that the vamp is playing, there would be a funk record of sorts. But that wasn't the intention of doing it. The vamp is like this: When you paint a picture, you're going to paint on something – a wall, a piece of cardboard, a stretched canvas, or whatever. Let's just say that the vamp is the canvas that you're painting your little knicknack on. And unless you do a good job stretching the canvas, it's not going to support the rest of the paint you're slopping on there.

Besides the tricky rhythms, you also have to pay attention to where you're going to play a note on the guitar; for instance, C can be played at several different places.

But you have something else to worry about, too. You have to say to yourself, "Is C the root?" If it's the root, you've got to play it one way. Is C the 3rd? If it is, you've got to play it another way. Is C the augmented 11th? Well, then it has to be played still another way. And you have to intone it to make it sound like the proper interval of the scale. That's something that many people neglect to do when they're practicing their instruments. You have to think, "What is the function of the pitch that I'm playing? How does it relate to the harmonic scheme that I'm operating in?" Because if you don't play it to sound like the interval that it's supposed to be, then it doesn't get the information across. And the melody works a lot better if you're thinking your intervals in terms of their function in the harmonic climate. That's what makes the difference between a good string section in an orchestra and a bad section. That's why sight-reading isn't usually an effective way to convey a musical idea. You aren't able to get the accents, or you don't get special little vibratos in there that make the piece talk. The idea is to make it talk. So to play my music isn't like coming in to do a quick soundtrack for a TV show. You don't walk in and play the footballs, pick up your double-scale check, and walk away. It ain't like that at all!

How fast do you expect your band's members to be able to pick up their parts?

That depends on the guy, because some people sight-read faster than others. And you learn to gauge your expectancies by what their abilities are. But I expect them to improve every year that they're with the band. It's a little bit like going to school. But the important thing is that whatever it takes to get it right, they eventually get it right – whether they spend a lot of time at home working on it, or whether they get banged over the head in rehearsal. Whatever it takes. They're supposed to get it right, or at least give their best effort to playing the stuff. If they don't, there are only two things that can happen: One, I have to give them easier parts, or two, they're not in the band anymore. I think it's fair, because the guys who want to be in this band want to do something other than play bonk, bonk, bonk. And unless they have a challenge, then they're going to get bored. So, there it is: I've got the challenge for them.

And you don't have to get mad at the players because the music doesn't sound just right.

Well, I can enjoy a bonk, bonk, bonk type of song, but I like to hear other things. My idea of a good time is a really simple-minded song followed by something that is out to lunch, and then back to simplicity again, and then out to lunch again. That's the way the world really is: It's not totally complex, and it's not totally simple. It's a combination of both. I also like to have a bonk, bonk, bonk track with complicated things going on above it, and vice-versa: A complicated track with really simple, long-tone melodies going on above it. It makes for the variety that keeps the interest going. And whether the bonk, bonk, bonk is provided by the drummer doesn't make any difference. I mean, you can have a bonk, bonk, bonk sensation just by having a tack piano playing quarter notes on a II chord – just playing a choppy rhythm like that, a real simple part, and everybody else going wild. As long as there's something that the audience can hear and say, "Okay, here's what we're relating to, and because we can understand this bonking over here, the rest of the stuff must mean that, because it's related to the bonk." You need to have a clue for the audience to start from before they can understand how fantastic the other stuff is. If there's no basic time, if there's no basic pulse where the audience can sense a foundation of some sort, then I don't think the piece works as well.

It sounds like a bunch of honking geese.

It sounds like "modern jazz"; you know, where there's a bunch of guys ego-tripping their brains out and just playing a bunch of poot, which, when combined, cancels itself out into this kind of little, brown cloud of nothingness that doesn't make any difference.

Read by OCR software. If you spot errors, let me know afka (at) afka.net