Scott Thunes. Requiem For A Heavyweight?

By Thomas Wictor

This page below was resqued from the Mike Keneally Band website www.cidanka.nl/keneally

SCOTT THUNES

REQUIEM FOR A HEAVYWEIGHT?

By Thomas Wictor

Bass Player Magazine, March 1997

(©1997 Bass Player Magazine)

Thanks to Lloyd Thayer for sending me a Xerox, and thanks for a great tape. Check out Nobody's music on The Nobody Website. -Tal

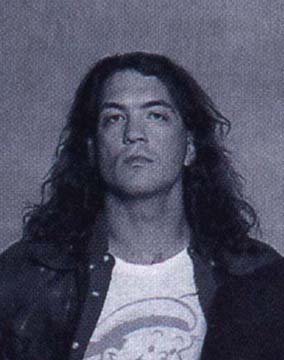

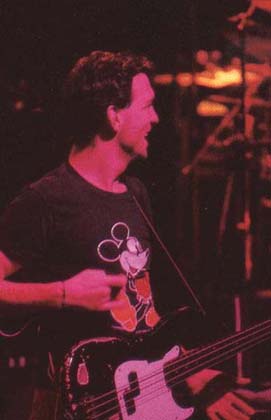

If you've never heard Scott Thunes play the bass, you can't appreciate how far the instrument can be taken. Thunes will dispute that notion, of course-he takes issue with the idea he's a great bassist. The former Frank Zappa sideman (whose surname is pronounced TOOness) is a contrarian of the highest order. He disagrees with almost any statement of a declarative nature, at least when it concerns his role in music and his approach to the bass. He' s of the opinion that much of the brilliant live work he recorded with Zappa is riddled with mistakes, each of which he's apt to point out in exacting detail.

If you've never heard Scott Thunes play the bass, you can't appreciate how far the instrument can be taken. Thunes will dispute that notion, of course-he takes issue with the idea he's a great bassist. The former Frank Zappa sideman (whose surname is pronounced TOOness) is a contrarian of the highest order. He disagrees with almost any statement of a declarative nature, at least when it concerns his role in music and his approach to the bass. He' s of the opinion that much of the brilliant live work he recorded with Zappa is riddled with mistakes, each of which he's apt to point out in exacting detail.

Raised in San Anselmo, California, Thunes took up the bass at age ten, when his mother and guitarplaying older brother decided the family needed a bassist. His burgeoning skills earned him an early admission to the College of Marin at age I5, where he studied jazz and discovered the works of classical composer Béla Bartók. Simultaneously, he was exposed to the new wave band Devo-a revelation that eventually knocked him free of his jazz-based moorings. Following a failed bid to enter the San Francisco Conservatory of Music as a conducting major, he parked cars and played in local rock and new wave bands, despite having decided that classical music was "the supreme expression of musical art."

In 1981, Thunes contacted Frank Zappa at the behest of his brother, who had himself tried unsuccessfully to audition for Zappa's group. Scott recorded some tracks in Los Angeles and was summoned back for the formal audition a week later. This session included improvising to arrhythmic tracks played on a drum machine, as well as performing the same song with two other auditioning bassists, the three of them competing face-to-face.

Once hired, Thunes toured and recorded with Zappa until 1988. During this period, he also recorded several albums with Frank's son Dweezil, forming a touring band with him in '89. In '93, Thunes left Dweezil's group, toured briefly with guitarist Steve Vai, and recorded and toured with the punk band Fear. In between construction jobs, temp work, and various local gigs in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, he also recorded with the Waterboys, Andy Prieboy, Wayne Kramer, Mike Keneally, and the Vandals, among others.

At the time of this interview, Scott Thunes was working as a doorman at the Paradise Lounge in San Francisco. You see, his resume doesn't mention that his musical career could be seen as one endless melee, or that he's been fired from as many bands as he's quit. And Scott admits most of the people he has worked with will never call him again.

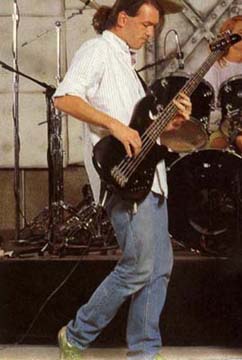

Even so, from an artistic standpoint, Thunes would be quite a catch for any group. Few bassists have played with his sheer scope and energy. If you compare two of Frank Zappa's better live records, Does Humor Belong in Music? and Make a Jazz Noise Here, for example, it' s hard to believe the same person is playing the bass. Scott's greatest gift is probably his ability to combine music theory with a natural exuberance on the instrument, resulting in a melodic, improvisational, emotional, and absolutely free voice that's unique and impossible to duplicate-despite his claims to the contrary.

Thunes reluctantly agreed to talk at his Marin County home, suggesting I come hang with him for an afternoon before the formal interview. Some of his former colleagues had warned me to beware of his abrasiveness, regaling me with mindboggling stories of his antics on and off the stage. Although opinions about Scott varied, one universal observation stood out: Thunes has an atavistic loathing of stupidity and smallmindedness, an attitude that could hardly have served him well in Los Angeles. At his house, we spent the first afternoon drinking coffee and chatting about films, music, art, and travel. We read aloud to each other from our favorite writers, went for a couple of walks, and listened to some CDs. The actual interview took place two days later. It was, sadly, without incident-although it was oddly thrilling to be called "Pookie," a name he gave me after we had been together a scant I5 minutes. As for the larger question, whether or not he's really through with the business...well, Frank Zappa himself also stopped touring in 1982. And in '84. And in '88.

You've said you have a problem being called a bass player. Can you explain?

You've said you have a problem being called a bass player. Can you explain?

Sure. When I learned how to play the bass, it was by default; I didn't really choose it for myself. When my mom brought one home, I was too young to appreciate any musicality about it-so I stopped playing within six months. I started up again because I saw my brother and his friends having so much fun, and playing the bass became a way to get into music-a way for my musicality to be expressed.

Within a short time, I exhibited talent for the instrument. In college, I was in the jazz band, orchestra, and wind band; I was learning tons of stuff. But I never thought of myself as a bass player; I was a musician. The actual role of the bassist does not interest me, and I don't know how it could interest anybody else. It's the ultimate non- glory position. Singers, guitar players, drummers, bass players-that's how it goes, in order of importance. Though the function of the bass is very important in a rock band, I've never ever been able to perform that function without irony.

But lots of people listen to your work and say to themselves, "Compared to him, I'm not a bass player."

Well, I hate to call them fools, but they don't know anything about music. What does it matter if you're a bass player? Pick another instrument you can express yourself on. I express myself on the bass because I've been playing it for 25 years. Visualizing its fingerboard is simple for me. It's simpler than the guitar, which has that third between the G and B strings that throws me off. The joy of playing the bass is having my voice come out on an instrument; I don't understand how that makes me a bass player. I also can't understand how that makes me a chosen role model, because it's the voice that's important, not the instrument. Everyone's trying to make the bass the voice. Stu Hamm playing the "Moonlight Sonata?" It's an ugly sound-don't do it! Step away from the bass! If you think the sound of the bass is more important than your own personal voice, you've missed the point of music completely.

Couldn't what you do on the bass be considered as having the same impact as Stu Hamm playing the "Moonlight Sonata" without the flashiness?

Couldn't what you do on the bass be considered as having the same impact as Stu Hamm playing the "Moonlight Sonata" without the flashiness?

That's got to be impossible, because I was not the first person to do what I do. I got it from somebody else. How come people don't listen to that person as well?

So who is that person?

John Paul Jones. He was my role model in the meshing of riffing with a personal melodic voice. When he was given a chance, he played melodies. And I know he's not the best bass player in the world, but neither am I. He wasn't supposed to be a great bassist. Most guitar players don't want a great bass player to play against, because they don't want the complicated dynamic interplay; they prefer more of an orchestrated interplay. That's what I performed: an orchestrated interplay with the other instruments. Most of the time guitar parts are fairly rigid, giving me tons of room to be fluid. And it's unfair I should be given even slight credit for something I don't feel pushed the boundaries of the instrument.

Do you repudiate the idea that your playing is of any value, that young bassists might look to you as a role model?

No. Yes. [Laughs.] I do not repudiate the idea that my playing has any value-just that I'm a role model. I can't be a bass player, I don't want to be a bass player, I have no interest in being a bass player; I don't want to fulfill that role. I want to be Scott Thunes, who has a voice. The music has always been my role model. And if there isn't anything juicy in it, I don't have anything to play against.

That's what John Paul Jones did: his voice was heard in conjunction with all the other voices. And that shouldn't have worked, because Jimmy Page, who's one of my favorite guitar players in the universe, is not a very good guitarist. But he's got great ideas, and he attempts to perform them.

Even if you're not a role model, there are people who would kill to play on the records you've played on.

Then kill! Go ahead and kill! [Laughs.]

There are also a lot of people who think you're an idiot for throwing it all away.

I didn't throw anything away! They threw me away. I didn't leave Los Angeles until I couldn't get a gig for two years. I did stay after I wasn't needed anymore, though, but I was with a girlfriend, I was in love, and I was having a good time. But you don't kill for a musical gig- it's not worth it! If you're going to school to learn how to be a musician, you're not learning how to be a rock star, and you're not learning how to be famous. You're learning to play music- that's it! It doesn't mean you get a band, it doesn't mean you hook up with friends ... it doesn't mean dick! You spent $5,000 on school? Great! That means you spent $5,000 on school. Now, get a job. And I don't mean in the musical world-I mean get a job.

You referred to yourself a couple days ago as a "musical has-been." Since you're a doorman at a club now and you're looking for work in the computer fleld, can you see how some people might see that as a tragic waste?

You referred to yourself a couple days ago as a "musical has-been." Since you're a doorman at a club now and you're looking for work in the computer fleld, can you see how some people might see that as a tragic waste?

No, because it's their fault. It's the audiences fault for being party to rock bullshit-for accepting the false truths that leaders of rockbands present to the world so people will think they're cool. If they only knew what these people are really like ... nobody deserves anything, especially not these people. I mean, I don't deserve what I got from Frank. I truly understand for myself that it was an absolute fluke of timing and nature that Frank wanted what I had to offer at that point in time. I'm a good bass player, fine. I'm a great bass player, great. Think whatever you want. But I'm Scott Thunes first and foremost, and that's where most of my problems come from. I deserve the happiness I can get from my chosen life, but not musical glory. I do not deserve musical glory. No musicians do, unless they are golden. And I don't know anybody who's golden.

What about if you have ability and an original approach? Don't you deserve to be heard just based on your skill?

Where? Where are you going to find a group of people I could work with and express myself within the confines of happiness? All of these CDs you've listened to were born from almost total emotional degradation, and I'd rather not touch the bass again until I can be happy doing it. I would much rather make $8 an hour work- ing at a club than go out on the road playing Make a Jazz Noise Here-type music and being, away from my wife. Anyway, music doesn't pay. If I can make more money working at a computer company that's doing interesting stuff, and if I can be happy at home every night, and if I've already played with Frank Zappa, where else is there to go?

If you won the lottery today and never had to work again, would you still be interested in music?

Oh, absolutely-but not the bass. I'd orchestrate. I would write pieces for other people to play, and I would sit back and watch. And there would be no bass player in my music. If I had my druthers, I would never, ever write for a rock band. I have no interest in writing songs. Being in a band isn't worth it. Most bands don't deserve to be together; they don't have enough songs to present to the world, and they don't deserve to have their music presented to the world. You are a lucky motherfucker to be able to stand onstage for even five seconds and have people stare at you. Ninety-eight percent of the bands out there do not deserve it for a sec- ond, let alone for an entire career.

Wouldn't it be a shame if people didn't get a chance to hear what you have to offer?

They have a chance. Those aIbums are out, and you can buy them. What else do they need to know? How many more recordings of my performances do they need to hear before they get it?

As many as possible?

No. If people hear more albums, will they learn more? Would they even understand it? Because all it is, really, is music theory. What I learned in music school was that in modern music, you can play any note against any chord and make it mean something. If you don't know how you're using it, or where it resolves, you're an idiot-you shouldn't be in music. I learned a couple of simple laws, and I utilized them. If you can't get that from two or three improvisatory bass lines of mine, you're not going to get it in two years of schooling. It's going to be shoved down your throat, and you're still not going to get it.

Thunes talks about the notorious 1988 tour of the Zappa band, the demise of which he is reputed to have caused. It takes him almost half an hour to explain. He describes a secret world of "Clonemeisters," "Magic Words," and smoking and nonsmoking buses-an exotic milieu spoiled by unbelievable pettiness, mean-spiritedness, poor judgment, spite, and bruised egos. He has no problem naming names, although it's clear that despite his jocular tone he takes no pleasure in reliving the experience. The awful childishness of the Mutilating of the Laminate and the Cake lncident, for example, illustrates the inadvisability of working and touring with people for whom one feels nothing but personal animosity. Ironically, many consider the '88 band to be one of Zappa's best, strictly in terms of pure musical prowess.

Thunes talks about the notorious 1988 tour of the Zappa band, the demise of which he is reputed to have caused. It takes him almost half an hour to explain. He describes a secret world of "Clonemeisters," "Magic Words," and smoking and nonsmoking buses-an exotic milieu spoiled by unbelievable pettiness, mean-spiritedness, poor judgment, spite, and bruised egos. He has no problem naming names, although it's clear that despite his jocular tone he takes no pleasure in reliving the experience. The awful childishness of the Mutilating of the Laminate and the Cake lncident, for example, illustrates the inadvisability of working and touring with people for whom one feels nothing but personal animosity. Ironically, many consider the '88 band to be one of Zappa's best, strictly in terms of pure musical prowess.

Isn't the pleasure or release of playing in a great band enough to make someone strong enough to take anything, no matter how bad?

Show me a good band, and I'11 tell you why there's tension in that band. And for the people who perform it, music very rarely releases tension; it almost always increases tension. And music does not help you to be a nice person. Why should a good musician be a nice person? There's no connection there. Tension increases; we all have our issues, and everybody's human.

Frank was a special case. He put up with a bunch of shit to allow the 1988 tour to work- but he wanted all the juice with none of the blood. All of those albums I played on have blood on every track; there's danger inherent in everything on them. Even during the standardized performances, there was danger lurking behind every single note. I dig tension in my music, because I know from modern classical music that tension can coexist with normalcy. Frank was a big fan of that.

Once in Barcelona, someone in the band came up to me and screamed, "Don't you know what a privilege it is to play with Frank? How can you ruin his music?" I play a lot of lines; I pick chunks out of the air, and instead of playing bass, I play Scott Thunes's part in the orchestration. And of course the whole idea of being a bass player is not to overplay: you "play the bass." But I've never done that-and if Frank isn't asking me to do that, don't you ask me. So at that particular moment I got out my headphones and put them on, and I started listening to classical music while this guy's mouth went, [flapping lower jaw] Beh- beh-beh-beh-beh. It was delicious.

At the end of the tour, Frank decided he wasn't going to play anymore, because the rest of the band had told him they wouldn't go out with me again. When he told me that, I said, "I'll gladly quit." He said, "That's not the answer. I like you, and I like what you do -except for all the mistakes you've been making." Because every night onstage, I was surrounded by daggers and completely lost my concentration. For three months I was a wreck, and the music suffered because of my mistakes. Frank's only enjoyment was playing guitar solos, and those fell apart; he ended up not doing any. We also ended up not doing any more three-hour soundchecks. We'd play just two songs, and then he'd get out of there. He could not stand being in the same room with us. It was the worst possible combination of events for him.

If everyone had gotten along, would the music have been that much better?

Yes. We would have been happily intercommunicating.

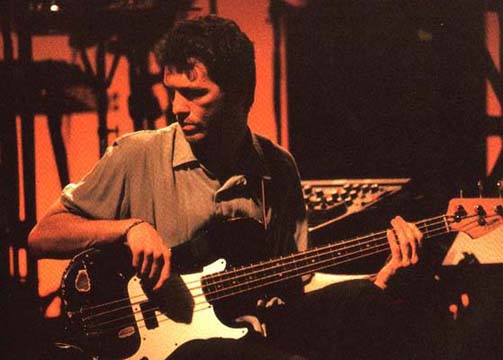

How did you develop your ability to improvise?

How did you develop your ability to improvise?

I was given jazz lessons at an early age. One of my bass teachers taught me how to listen to Ron Carter playing behind Sonny Rollins, and I later utilized a concept I learned-adding tone chords-in rock. Most of the time when I'm playing weird stuff against normal-sounding stuff, I'm adding a whole other chord. That's similar to polytonal or bitonal classical music, and jazz, because a lot of jazz chords are just one chord superimposed over a solo bass note or another chord. It's the simplest thing in the world. I just gave away $2,000 worth of lessons.

I know I should be playing way less. I shouldn't even have this knowledge. Bass players aren't supposed to have ideas; they're supposed to be functionaries. If you're a bass player in a rock band, you are by definition a moron- because you are doing nothing except what the song requires. With Frank, though, my job was to serve him. Frank had different needs at different times, and that's where the low-level functionaryism came in-and that's also where I was earning my money. The moments of improvisatory freedom are when I was able to do what nobody else was doing. The Scott Thunes Effect, baby.

Is this approach the sort of thing that led people to say you're hard to get along with? Your insistence on going your own way onstage?

No, it's definitely in my personal life. Onstage, stuff was turned into a negative only by people who didn't like that form of communication to begin with-who didn't want people to step out of their pre-determined roles. They didn't realize the unspoken bond Frank and I had in the string arena. But if I told someone to leave me alone, I was [in Betty Boop voice] "being abrasive." If you tell me what to do, I will get angry. If you say something stupid, I will get angry. If you attempt to drag my conversation down to a moronic level, I will get angry-and I will stomp out of the room. I need to hear beauty in verbiage and musicality. That's my requirement.

You've said you had problems with drummers, but on lots of the live recordings you and the drummer are very right. There's an echoing of rolls that's so dead-on, it seems almost like telepathy.

That's the stupidest thing I've ever heard! I'm listening and reacting to him-that's all you're hearing. As a matter of fact, I'm being led around by the nose. All I'm doing is saying to myself, "What is there to react to? I can listen to Frank, I can listen to the keyboards, but I know all the riffs. The only strange thing might be the drums." On the other hand, you might be hearing an orchestration we had worked out months in advance.

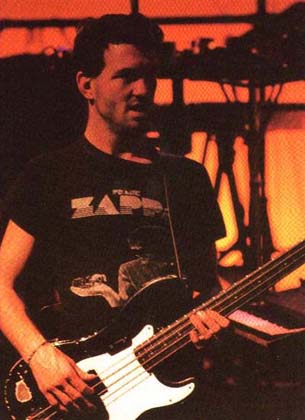

So how did you end up with Fender basses?

I heard Tom Fowler on Frank's album Roxy and Elsewhere [BarkingPumpkin]; he had a black P-Bass with a white pickguard, and he played with a pick. That sound intrigued me: it growled, and it was ugly. Yet he could play all of these complicated riffs, and it didn't sound overly technical the way he did it. It sounded ... really cool. In my first couple of years with Frank, I used Carvin instruments, but that wasn't my voice. The first year I used the P-Bass was 1984; around that time, Frank started letting me do anything I wanted, and what I did that wasn't rancid was good. And in '88, when he gave me complete and utter carte blanche, I shone in the ultimate ways a bass player can shine. I had the tone I wanted, I had the amplification I wanted, and I had the performer's arena.

You told me earlier you don't view yourself as an artist but rather as a flawed craftsman.

In the two days since we've discussed this, I've changed my mind. You're absolutely correct: I'm an artist. I'm a naive artist, like Howard Finster, who did the album cover for Talking Heads' Little Creatures. It's folk art-and from the way he paints, it looks like if he attempted to build a chair, it would be un-sit-in-able. My bass playing is un-sit-in-able. It's not meant to functionalize the four legs of the bass-playing experience. It's folk art in the most extreme and financially remunerative fashion. Frank chose me as his local spoon player; all I did was rattle around on my strings, cross my fingers, and hope I didn't get fired the next week.

What do you think of the idea that you saying, "I haven't done anything special on the bass," is really just an inverted way of saying, "I'm the best bassist in the world"?

What do you think of the idea that you saying, "I haven't done anything special on the bass," is really just an inverted way of saying, "I'm the best bassist in the world"?

[Blows huge raspberry and laughs raucously.]

What does that even mean?

Well, it's hard to believe you honestly think you're not a creative force on the bass.

I did not extend the realm of the bass. No way. If you're a good bass player, right now you could play everything I ever played, if it were written out and you practiced for a week. Great bass playing can take you to the top-but I'm not at the top.

My whole musical life has been one oddity after another. Everything I've tried to do hasn't worked, and when I try to do nothing, things come to me. There's no joy in being thwarted; there's no glory in the fight well fought and lost, especially in music. Music has found me unnecessary, but it has placed me here in happiness for the first time in years, so there's no sadness.

I have achieved something many musicians will never have: happiness. Everything else comes second. I don't want to come off like a hibernating Zen monk; it's not that I stepped down off the mountain. I spent ten years in Los Angeles thinking my $300 a week from Dweezil was the best I could get. I was depressed, but I did my job with as much aplomb as I could. And that's what most people want. Most people just want to be in a rock band. They want their musical ideas to be valid. I'd rather have my life be valid. My story isn't anywhere near as bad as people who have lost everything, because I never had anything to lose. I've always been searching for happiness, and I've found it. That's about all there is to say.